A Bigger Splash

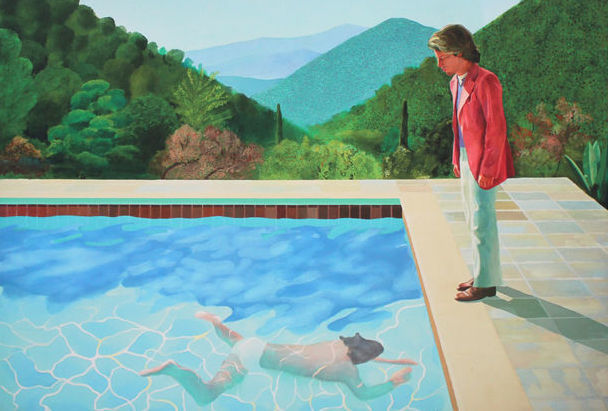

The Hockney work A Bigger Splash depicts a scene of apparent tranquility, where everything is in its place. The chair, the trampoline, the colors, and even the plants are well cared providing us with a normal scenario of the West Coast villas with pools of the Sixties. Yet it seems immediate to ask: what happened to the human presence? The woman, the man, the child or the old man, whatever the subject of the canvas was, where is he or she hiding?

In fact, in A Bigger Splash there is a clear reference to a dive, a leap, but human being is not mentioned. Even the shadow of the diver does not appear. So from a descriptive point of view, it is certain that the dive was made explicit by the presence of different colors and rapid brush strokes that contrast with the color of the pool water. But from a connotative point of view, the work recalls a fast, rapid scene that collides with the calm colors of

the surrounding landscape. But can the absence of ‘a human being’ make us perceive that something has happened at the narrative level?

On the other hand, we must not forget that the director Luca Guadagnino in the homonymous film A Bigger Splash staged a murder precisely drawing inspiration from the silent atmosphere of this painting.

In this article, I will reconsider the presence of water in Hockney’s paintings through a gender perspective, because by examining this canvas, it appears very difficult to find the typical intertextual script of a murder.

Since, precisely, there are no frames capable of encoding it in this sense. Indeed, it seems more likely that it is a script than a simple dive. Such it could be that the protagonist, after having dived, is still swimming in the pool even if this action is not made explicit. On the other hand, there are no traces that can tell us that it was a murder. In the case of a shot we would have seen blood mixing with water. Moreover in the case of a suicide, we would have noticed a noose, and so on. After all, we must remember what the swimming pool symbolized at the time.

Precisely in America, Hockney rediscovers a palette full of colors and the subjects portrayed by him immediately appear brighter and full of life, while remaining faithful to his key themes such as the exaltation of homosexuality, the contemplation of erotic love, and the indissoluble union between shape and atmosphere. America and the fulfillment of the American dream are represented in his paintings like specifics objects: real swimming pools.

In fact, Hockney in California discovers that almost each resident got it one, regardless of the social class they belong to. Whether small or large, not matter which size, this reality is enormously opposed to the English scenario from which the artist comes. There, having a swimming pool was instead synonymous of opulence and luxury limited to a small circle of people. Hence the decision to analyze and understand these new spaces, also immortalizing the flow of water with them: this is how the Splash series was born between 1964 and 1971.

A Bigger Splash was painted between April and June 1967 when Hockney was teaching at the University from California to Berkeley. This canvas is followed by two analogous paintings by Hockney: A Little Splash and The Splash. In A Bigger Splash we see a diving board that juts out from the edge towards the foreground of the painting and “the dip” is represented by blue patches combined within white lines on the turquoise water.

The background is a modern villa with a typical American setting that looks similar to the shots of photographer Julius Shulman. Here, furnishings in soft colors and large windows like sliding doors in which the surrounding tropical plants are reflected. This work depicts a scene of apparent tranquility, where everything is in its place.

In A Bigger Splash the water, in its simultaneous fluidity and tension, in its coexistence of “surface” and “depth”, is, therefore, a metaphor that represents the transgressive act of the “dive”, as the human being who breaks the rules. Instead of death, as Guadagnino reads, A Bigger Splash seems to suggest strength, self-esteem, and great adherence to life. Water, in its simultaneous fluidity and tension, in its coexistence of “surface” and “depth”, is a perfect metaphor that fully reproduces the transgressive act of diving, as of the human being who breaks the rules.

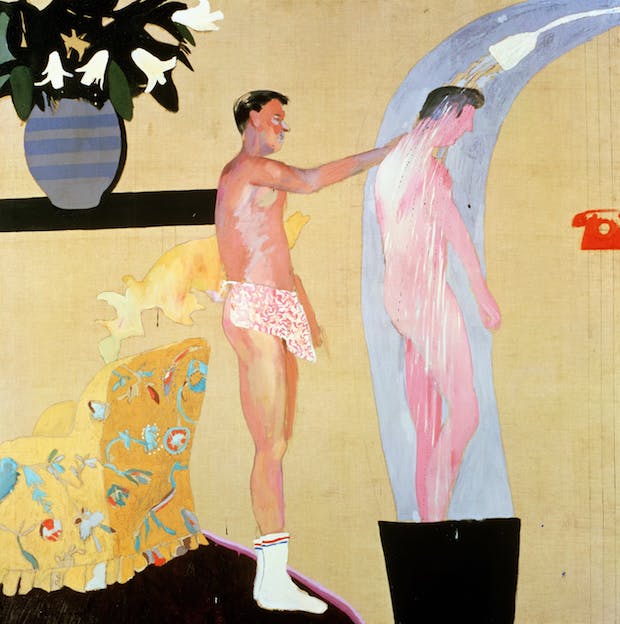

We must always keep in mind the attitude of the young Hockney who perceives the swimming pool as the perfect reflection of the American society of those years, in which the erotic power reveals an atmosphere free from the social pressures of post-war Britain. In particular, we refer to Two Men in a Shower from 1964 or the Paper Pools series. Here, naked male bodies often appear on the canvases in the form of statuary models from Ancient Greece. In this otherworldly dimension, the swimming pool becomes “the entertainment Mecca”.

The swimming pool is clearly just an ornament to reflect on those who live it, on the Hollywood protagonists of those years, exalting their status symbol. But, above all, imposing themselves as a means to express erotic desire, voyeurism, and an embryonic state between nature and culture. “For Hockney, the surfaces of the pool burn in the California sun. Within desire”.

Another very interesting project that immortalizes Californian society from the 1940s to the 1980s is Backyard Oasis: The Swimming Pool in Southern California Photography. The exhibition is curated by Daniel Cornell in 2012, with the following artists including Bill Anderson, John Baldessari, Ruth Bernhard, David Hockney, Herb Ritts, Ed Ruscha, Julius Shulman, and Larry Sultan. Their works of art had one aim in common: proposing the swimming pool as a multipurpose symbol, capable of representing in which the rise of celebrity fame, the design of the avant-garde architectural landscape, and the cult of the body and male nudity can be fixed up together.

With regard to the latter, it is impossible not to mention the famous photographer Bob Mizer, who between the 1950s and 1960s was the spokesperson for the new Beefcake model (which can be translated into “big steak” or “nice beef”). The term indicates the muscular, naked male body or semi-nude portrayed in very small costumes, just like it happened with pin-ups. Other representations of the society of the time can be found in the recent productions of American Crime Story‘s Assassination Versace or in Hollywood by the famous Ryan Murphy.

These are just some of the countless cinematic examples that treat the pool as a place beyond social conventions. Gianni Versace himself in his Miami villa loved to take refuge with his sweetheart or where his own executioner Andrew Cunanan was usually swimming carefree in complete nudity. In Hollywood, the space of the private swimming pool is the meeting place par excellence for homosexual artists, directors, and set designers. Here they could indulge in effusions and admiration of their own bodies without fear of any media interference.

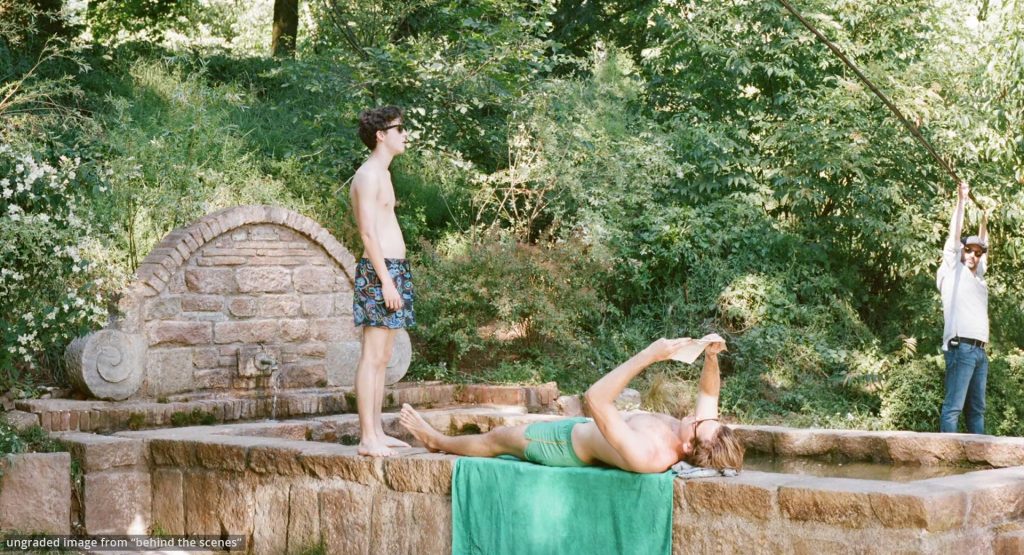

This long attention given to the male body, to nudity but, above all, to the ancient ideal of καλὸς καὶ ἀγαθός is described in a mainly Platonic key in Call Me By Your Name by Guadagnino. This is the third and last film belonging to the Italian director’s Trilogy of Desire after I Am Love and A Bigger Splash inspired by

Hockney’s canvas of the same name, reinterpreted in a thriller key.

In Call Me By Your Name the bite of a peach, a bike ride, and sometimes a barely hinted contact tease the love story between the two protagonists. Eliot, a young teenager, and Oliver a Ph.D. student in archeology. In numerous sequences, the adoration and contemplation of Oliver’s naked and statuary body are compared to the physiognomy of classical busts. In one scene, in particular, the young Eliot, is eager to see him naked and to seduce him. And he refers to Oliver with: “Let’s go to take a bath”. Since this moment, their story and erotic yearning will begin.

There are several legends and sources about the reflection on water, the origin of life, the discovery of the self, and one’s own sexuality. Just think of Thales, one of the first philosophers in history, who believed that the flow of water corresponded to the initiatory principle; or the legends that tell about the dead being ferried into the river Lethe, who seem to forget everything after drinking the water of the river, returning to a primitive unconscious state.

The shower, the dive, and water, in general, are understood as phenomena and representations of rebirth and rediscovery of oneself. Still, in the Sixties, it must be remembered that we are witnessing a progressive opening of public bathrooms and spaces to be shared, where the lack of distinction of social classes has generated a fervent sexual exploration of a universal type.

Moreover, even today we speak of “fluid sexuality” perhaps as a reflection of the theory already put in place by Bauman in Liquid Love and Liquid Life, for which it is necessary that the human being, both in love and outside, defines himself as fluid and at the same time versatile to marry and blend in with a constantly changing society. In a perfect “liquid society” described by Bauman: “Hockney, the surfaces of the pool burn in the California sun. And with them also desire“. (Heardman 2018)