THE TIME WHEN ITALO CALVINO FELL IN LOVE WITH DOMENICO GNOLI

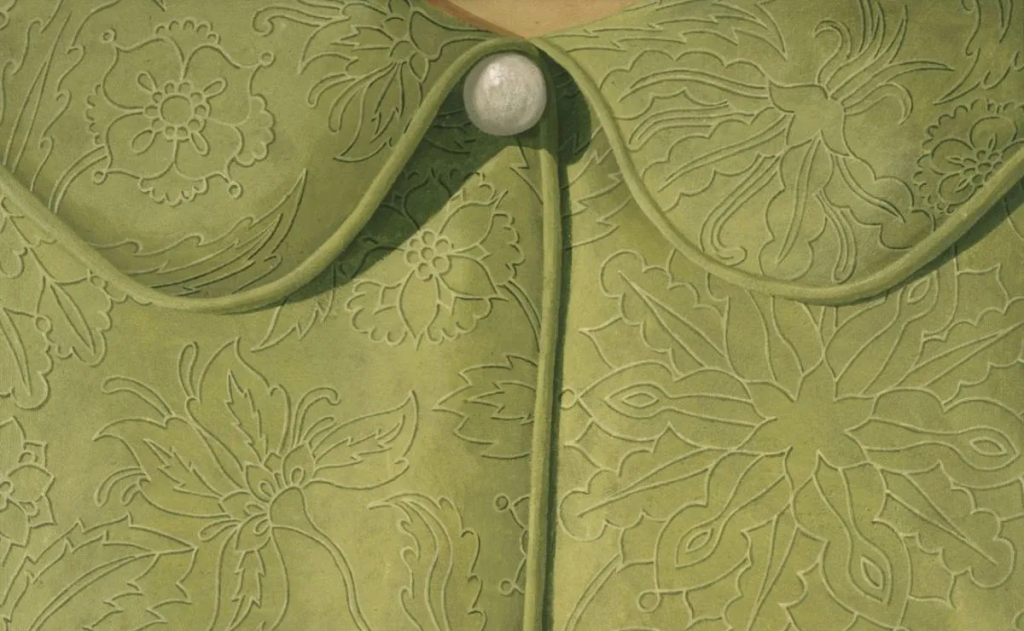

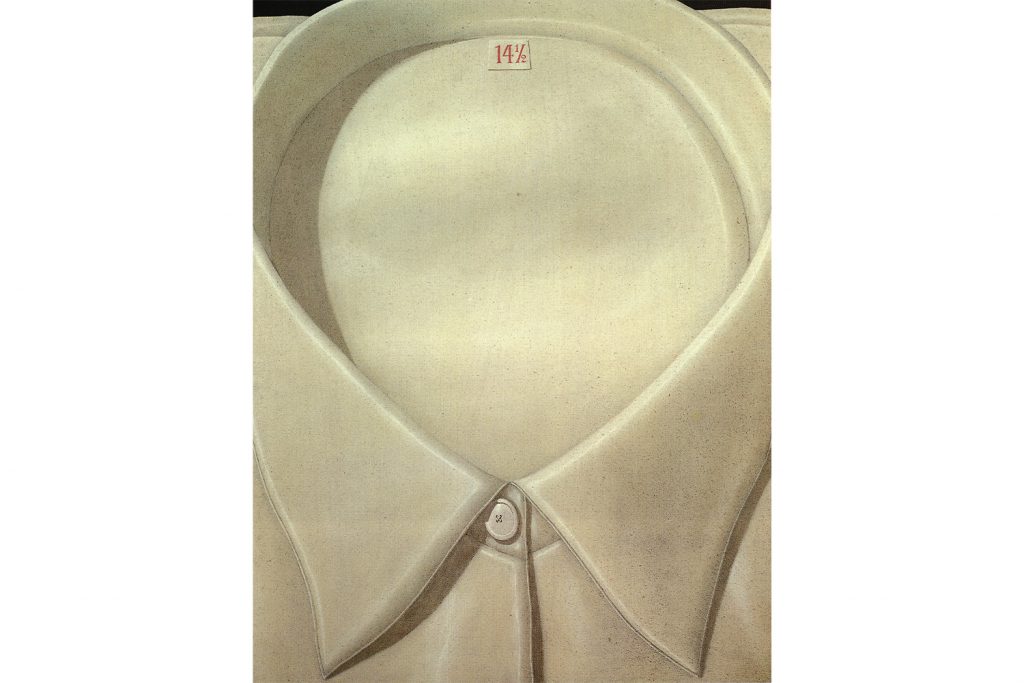

Quattro studi dal vero alla maniera di Domenico Gnoli (Four Studies from Life in the Manner of Domenico Gnoli), is the title of one of Calvino’s finest essays, which collects four short writings on four paintings by Gnoli depicting: a woman’s shoe, a button, a man’s shirt collar, a pillow.

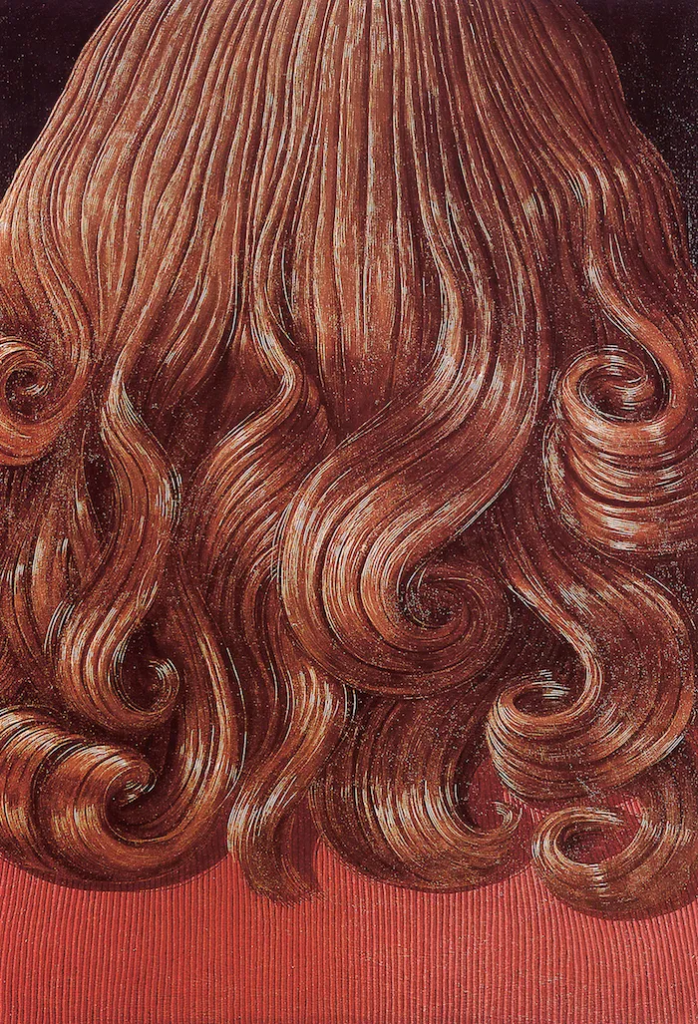

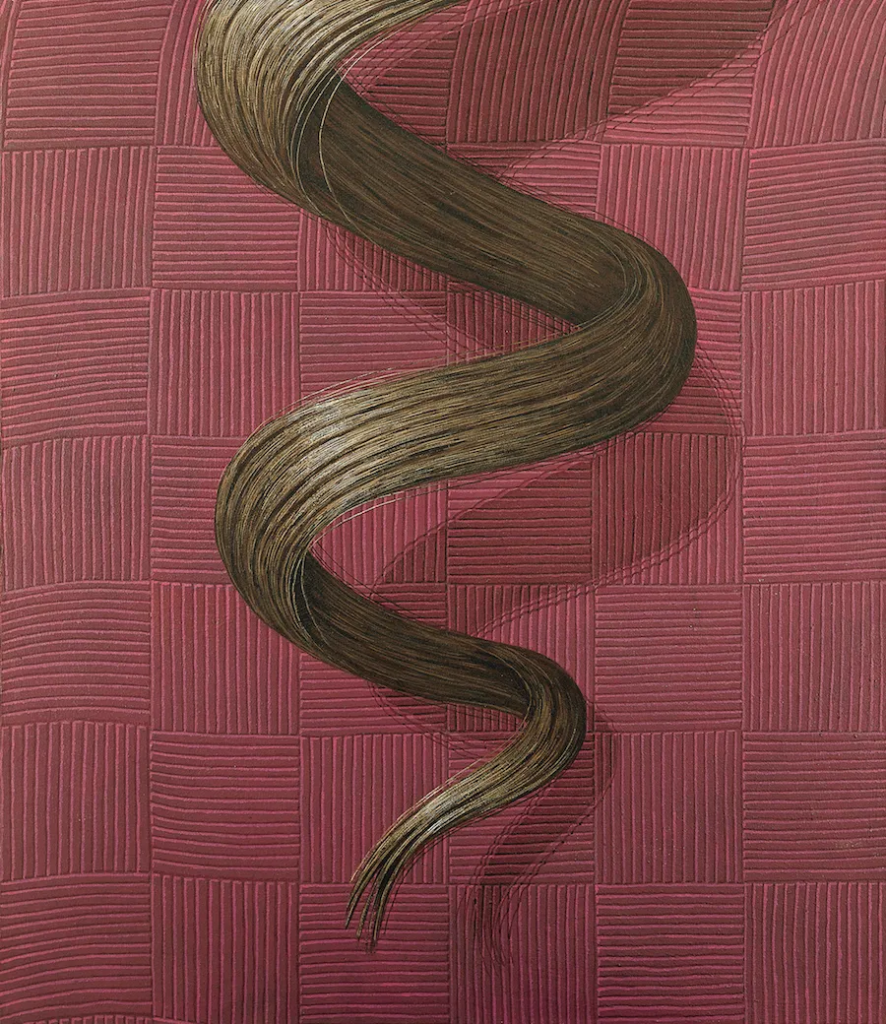

Each of these ‘simple’ painted objects are actually depicted on canvas as if they were huge details, staggering monuments, as if Gnoli with a magnifying glass has chosen what we should look at.

He could well have completed the work by inserting the human presence, drawing for example not only a woman’s shoe but also the instep, the leg, the human presence wearing it.

Every single element is ‘allowed to live’ in Gnoli’s paintings and in Calvino’s written works, that detail on which one focuses is considered – to paraphrase Musil – as a habit of thought and an attitude of life that makes its exemplary power influence everything else.

These objects suffice themselves, they are independent, alive, but above all, both Gnoli and Calvino propose them in a new light. Both invite us to rethink our everyday reality, working by value addition, to associate even to an embroidery on a tablecloth a value that is not its own.

Think of Gnoli’s men’s shirt, which, in its being both object and defined space, possesses a geometric autonomy.

“Not only is the shirt no longer a garment, it even becomes a space, a place in which to draw lines and axioms. The shirt eludes any comparative method, it resembles nothing, so all that remains is to define it as a table, according to an apparently sterile language: the geometric one.”

In Calvino’s text, the shirt is defined as: “the amphitheatre as a very low truncated cylinder inscribed within a truncated cone of irregular shape (perhaps with an elliptical base)”.Gnoli’s bed, collar, chair and, more generally, his works can be said to be precise and defined works, which respond perfectly to the three criteria of exactitude set out by Calvino: “1. To realise a well-defined and well-calculated design of the work; 2. To evoke sharp, incisive, memorable visual images; 3. To generate language that is as precise as possible in terms of vocabulary and in terms of rendering the nuances of thought and imagination”.

The coincidental, well-described objects are no longer what they were before they were depicted. They have become like Pomian’s semiophors: emptied things

of their primary function that they acquire a new utility and value. Franz Steiner in Theories of Economies argued the uncertain entity of these semiophors, far from practicality, from tangibility. “The more meaning there is in a thing, the less useful it will be”. This brings us back to the hierarchical system of vertical matrix whereby at the top we find the God, the powerful, and at the base of the pyramid the humble, or the ‘simple’ community that has to do with everyday reality, with the real world. The further one moves away from God or any power figure, the more one goes towards the visible. The higher you go, the more you have semiophors around you. Every attempt is made in Pomian to define these half-empires as masters of the field of the invisible, of the imaginary, of what is ‘infinitely vast’.

And it is interesting how it is precisely from an object, from a thing, from a precise and delineated detail that represents the ultimate in concreteness that one can speak of abstraction. How can something specific be the key to the understanding of the indefinite? Leopardi knew something about this, yet the poet of the infinite claimed to deal with this theme of the vague at 360 degrees without starting from an object of non-sensible reality. However, as Calvino shows us, always speaking of exactitude, Leopardi does the opposite of what he says. The poet from Recanati actually formulates an accurate and precise description; the author cannot help but make use of exactitude to delineate an abstract image. Infinite pleasure is the goal of strict descriptivism. What is distant and unknown starts from Recanati, from his home, from the analysis and study of the objects and places he always had before his eyes. The vague is ‘nella chiusa bottega alla lucerna’, ‘su la piazzuola in frotta’: it is that hedge.

Calvino knows this because when he writes a story, he starts it with a description of an object or a place, which, as it is described, ends up being just an appendix. The plot and the life of the story is what revolves around the object. “The relationship between that given subject and all its possible variants and alternatives, all the events that time and space can contain. It is a devouring, destructive obsession that is enough to block me. To fight it, I try to limit the field of what I have to say, then to divide it into even more limited fields, then to divide them again, and so on. And then I get another vertigo, that of the detail of the detail of the detail, I get sucked into the infinitesimal, the infinitely small, just as I used to disperse into the infinitely vast)’.

The ekphrasis of Gnoli’s works proceed in this geometry of sufferings, in which the Genoese author tries to come to terms with his own collections.

The pillow, it is: “the only form in the world that unites the stability of the square (or rather the rectangle) and the fullness of the sphere (or at any rate of a body convex and curved throughout its surface)”. Movement and stasis, the sign of the passage of life on things: the footprint of a presence. “Absence, however, does not appear as a negation of presence; on the contrary, it is precisely the latter that is the effect of a generalised absence”.

Gnoli’s Beds series is the exact translation of what has just been said, the artist paints beds made and unmade, detailing their contours, the patterns on the blankets, the wrinkles on the pillows. Who has passed by is irrelevant, what counts is the action that has taken place, this continuous emptiness, this absence that wants to be filled by the viewer, the visitor. The imagination of the viewer is fundamental, it forms presence where there is none. Gnoli continually paints a fantasy starting from the everyday, the same theory that Calvino in a RAI interview said was the prerogative of modern man to oppose routine one must use imagination.

Titta da Girolamo in The Consequences of Love said it over and over again, for him the worst thing in the world was to have no imagination. Because life, already boring and repetitive in itself, becomes a deadly spectacle in the absence of imagination. However, the Genoese writer argues the need not to fall into the trap of the eternal quest for abstraction, because ‘imagination in power’ can do damage to the individual by concealing his habits, tasks, work, family and friends. An abstraction is only possible through a slow, complex, correct and systematic labor limae, capable of generating a language that is not approximate, but precise and exact.

Calvino was terrified of the misuse of words in communication, not only referring to others, but especially to himself. If during a conversation it often happens that one does not pay too much attention to the use of language, in writing this does not happen. One can write as much as one can delete and edit.

Calvino proposes as a fight against the ‘plague of language’, the uniformity that flattens everything, literature and art capable of counteracting this ‘disease’ through defined representation.

Imaginary realism is rooted here, starting from everyday life and arriving at sensible reality, two worlds that coexist. Both artists, Gnoli and Calvino, possess what they talk about, paint or describe to such an extent that they can reconstruct it ad infinitum.