The Myth of CiucciaNebbia, by Gaia D’Arrigo

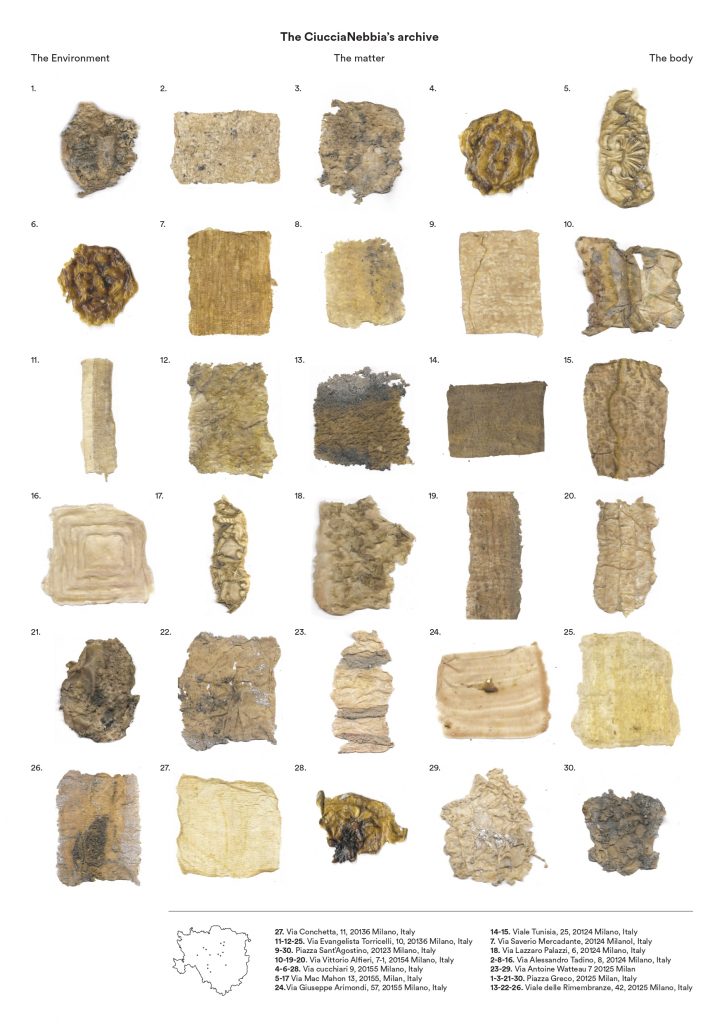

Gaia D'Arrigo‘s The Myth of the CiucciaNebbia is a layered, multi-phase art project. It is a simultaneously analytical and intiuitive-creative, art-based research that addresses an urgent and painful contemporary problem: the poisoning of the environment in which we live, of which we are a part and which we have created.